What is unusual about the word pulchritude. It means beauty, especially the beauty of a woman. Pulchritude is certainly not an attractive word. How about the word diminutive or unwritten. Diminutive is not a short word, and unwritten is a word that can obviously be written. What is distinctive about these words is that they are all words that have been described as ‘not being themselves’. What they appear to mean is different from what they actually mean, their structure or appearance contrasts with their meaning, or they contradict themselves.

The term for such words is heterological, meaning something that does not describe itself, A study of such words is an esoteric one, of interest to language academics or lexicologists.

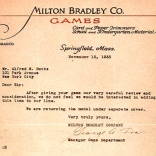

As this post is a little on the dry side (except perhaps for the bit about oxymorons etc at the end), I thought to lighten it up with a few cartoons on the subject of language and learning.

Words that do describe themselves are called homological or autological words such as finite, meaningful, numberless, pronounceable, readable, unhyphenated, thing, and visible. Good examples are grandiloquent meaning pompous or extravagant in a way intended to impress, and sesquipedalian meaning long-winded or characterized by long words. Such words are actually hard to find.

Are not almost all words heterological words? I suppose they are.

Misleading Words

Apocryphal sounds as if it’s a story of great importance whereas it means a tale of dubious authenticity.

Belladonna may mean beautiful lady in Italian and sound like a stylish woman, but it’s the poisonous plant deadly nightshade.

Bemused might sound like amused, but it means puzzled or confused.

Benighted suggests someone who is honoured but it refers to someone who is ignorant or lacking in morals.

Bodkin ought to mean a little body but its a large needle without a point.

Bucolic surely means chocked up if not a severe illness, but it refers to an idyllic rural life or it suggests a pastoral way of life as with shepherds.

Crapulous sounds dirty but it’s excessive indulgence, intemperance.

Callipygian sounds as if describes a feature of an animal but it means well proportioned buttocks

Crepuscular refers not to a skin ailment but to creatures like bats or rabbits that are active in twilight, the period before dawn or after dusk

Decimate historically this was to kill one in every ten soldiers but nowadays it means destroying a large portion of something

Disinterested means to be impartial or unprejudiced, but it is often confused with uninterested, that is to be unconcerned or not bothered with something

Enervate is to be lacking in energy, though it sounds like the opposite, or even to annoy someone.

Enormity might be something to do with size or magnitude, but it’s actually about the seriousness or extent of something that’s bad or morally wrong.

Erstwhile means former not as often thought esteemed.

Fungible sounds like it describes a spongy fungus, but its a legal term describing goods or commodities that can be replaced by equivalent items.

Hiatus is not a commotion or a ruckus, but a pause in activity.

Inflammable suggest it can’t be set on fire, that it can’t be burnt, except that it means it can. Flammable and inflammable mean the same thing.

Ironclad has nothing to do with somebody dressed in armour, but it describes arguments that are impossible to disprove or contradict.

Mawkish sounds as if it might be to do with mocking someone or something, but it means to be excessively sentimental

Mordant might suggest someone who is ponderous or broody but it actually means humour that is biting and incisive. It also refers to a substance used to fix dyes to cells and textiles, and to a musical notation.

Noisome is to have a very disagreeable smell. Nothing to do with being noisy,

Nonplussed sounds like it means not caring too much about things, but it means very surprised or confused.

Nugatory must be something to do with nougat but it means futile, trifling, or having no value.

Orrery might be an animals nest or lair but it’s a mechanical model of the solar system showing the relative positions and motions of the planets.

Phlegmatic refers to a person who is calm, composed, unemotional, not as it might seem someone who gets easily excited or is animated.

Plethora means an excess of something, not an ancient Greek musical instrument

Priceless sounds as if it could mean cheap or worthless though it means the opposite, very valuable.

Prodigal looks and feels like the word prodigy which means a talented individual who invites admiration, but in reality means recklessly wasteful.

Prosaic comes from the word prose and means commonplace, lacking in imagination, dull, even though the word sounds elegant or ornamental.

Pulchritude sounds like ineptness or even a pustule, or refers to a rather large person, but as mentioned above it’s a showy word for beauty.

Saturnine was said to be the temperament of someone born under the supposed astrological influence of Saturn, but it nowadays means gloomy or melancholic.

Scurrilous could describe how some small animals move, but it’s the making or spreading scandalous claims about someone in order to damage their reputation.

Vomitorium contrary to what might seem obvious was the tunnel-like entrance in an amphitheatre or stadium.